(excerpt from Mugwumpishly Tendered: Essays from the Seasons of One Woman’s Life by Corinne Corley)

Good morning.

Ten days remain between us and December 25th, and as the steam rises from my coffee cup, I think of what I have left to accomplish. Three hearings, perhaps a fourth judging by a message left on Friday; a half-dozen presents to buy; the tree to finish decorating; and meals to cook, including finding a recipe for palatable gluten-free cookies.

As I raise the mug to take another sip, eternally grumbling, my eyes chance to fall on today’s banner headline. One word spans the columns, in three-inch type: Horrific.

When our suite-mate rushed into the office to tell us about the massacre in Connecticut, my stomach lurched. Dear God, not more children killed. As I sat in front of my computer screen, a wellspring of conflicting emotions flooded my chest: Those poor babies; that monster; how are the parents going to struggle through this? The children huddled under those desks: How terrified they must have been.

I sank back, back, back… two decades to the path I trod down a hall of Kansas University Hospital, behind a rapidly striding doctor. A path that repeats so often in my mind.

A friend had taken me to KU because I felt pains in my “right lower quadrant” and my temperature had elevated. Neither of us knew with certainty the signs of appendicitis. We each had memories of rudimentary instructions in first aid class. The pain with the fever seemed to suggest trouble. So off we went to the closest hospital.

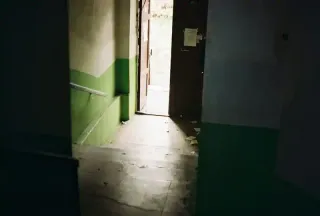

An overworked resident suggested that I might have hours to wait before lab results confirmed or dispelled our worries. I released my friend. No cell phones in 1981, but I assumed a nurse would let me call my friend to come get me when they decided I could go home. So I pulled my jeans onto may skinny legs, exited the exam room clutching the hospital gown closed, and turned right.

The emergency room corridors formed an inner square with the exam rooms on the outer perimeter and the nurses’ station sitting squarely in the middle. I could not know that precisely at the moment Bradley R. Boan entered the emergency armed with a shotgun and a bad disposition. He lurched into the very corridor which I traversed. Between him and me, Dr. Marc Beck strode, long-limbed and intent, chart in hand, probably not even watching ahead of him, oblivious to the fact that there would be no more Christmases, no more patients. No more life.

When the shotgun blast sounded, I dove down an intersecting corridor and ran towards what I believed to be the exit. I found only an abandoned waiting room, chairs strewn with jackets, coats and magazines. I stood against the wall, frantic, listening to the screams, the shoving of furniture, the barring of doors. A second blast, as Boan dispatched with a patient’s mother sitting in a wheelchair to the right of the entrance, savagely and senselessly.

And then: an eerie silence, punctuated only by the occasional ringing of an unattended phone.

I gazed at my own grim face reflected in a dark window. I realized that if I could see the reflection of the corridor, anyone coming into the corridor could see me. I dove into an examining room, where I waited for what seemed an eternity, alone, under the examination table, the door blocked by a cart that I had shoved in front of it.

The evening progressed: eventually, escorted to the dark parking structure in which KBI agents had shot out light after light, hoping to flush out the suspect whom they thought was hiding there. As it happens, he had long since fled, and would not be captured until he unleashed his fury on another place of healing: a church. He would be caught, tried, and unsuccessfully attempt to blame mental illness. Connection affirmed, film at ten.

As I sit in my dining room, 21 plus years later the terrible tragedy in Connecticut raises the hairs on the back of may neck. Grief draws tears: grief for children who’s e lives ended with the deadly aim of ruthless murderer. But grief also for the children huddled nearby under desks. Layer upon layer of pain will unfold in their minds, drawn forth as they mature, bubbles rising to the surface, or foaming beneath the cool plane of their passive faces. Time after time, they will ask themselves the question that lurks in the gloomy corners: Why them? Why not me?

Years after my encounter with a killer’s rage, I stood in the bathroom at my home in Winslow, Arkansas. The drug store kit had shown a solid “plus”, foretelling the birth of my son. Eyes met reflected eyes. The chill of winter surrounded me; the future loomed, with its sleepless nights, its momentary flashes of regret, its joys, its triumphs, its fears. As I stared into my own future, I felt the surge of survivor’s guilt that I can never shake. So much has happened to me. A chaotic childhood. A few lost years, drowned in single malt. Some ravaged relationships, a few that left scars, some that left bruises that faded only in the corporal world. Got run down, left for dead…

And yet, still living. Where others bled and died, I rose, a crippled Phoenix, with tattered feathers, and flew on, sometimes knocked off course, but still flying. Why them? Why not me?

The coffee pot sounds three bells, telling me it has shut off. The crickets which sing in my inner ear raise their voices. The rest of the house stands silent. One glance tells me that the headline has not changed: 20 children sill lay in the morgue, six adults to watch over them forever. In an hour or so, a friend will pull into my driveway, and we will go sit over brunch, warm food in our bellies, steaming tea in a pot, chasing away the cares of the week with the same sort of ease that a lunatic ended the lifespan of of twenty-six innocents.

Mugwumpishly tendered…

Corinne Corley lives in a tiny house on something like an island somewhere in California where she is an essayist and writer and legal-eagle. You can follow her blog at http://themissourimugwump.com